You've heard the pitch a thousand times. Your COBOL systems are legacy. They're risky. They're expensive to maintain. The developers who understand them are retiring. The solution? Modernize. Rip out those ancient mainframes and replace them with shiny new cloud-native microservices built on the latest tech stacks.

It's a compelling narrative. It's also essentially wrong.

The enterprise software industry has spent decades—and convinced organizations to spend billions—chasing a fundamentally flawed premise: that the value of your systems lies in the technology they're built on, not the business logic they contain. This misconception has fueled one of the most expensive and failure-prone initiatives in corporate IT: large-scale modernization projects.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Modernization Failure

Here's what the vendors won't lead with: 66% of technology projects end in partial or total failure, according to the Standish Group's CHAOS 2020 report analyzing 50,000 projects globally. For insurance companies, only 42% of modernization projects meet the original budget, and 82% take longer than expected. According to Gartner research, 75% of IT projects fail to meet objectives due to time and budget overruns.

Projects that were supposed to take 30 months stretch into multi-year odysseys. Budgets that started at $10 million balloons to $30 million or more. And at the end, organizations often discover they've recreated their old system's functionality—along with its problems—just in a newer syntax.

Consider Commonwealth Bank of Australia's experience: when they replaced their core COBOL platform in 2012, the project took five years and cost $750 million—significantly over original estimates. While the bank ultimately succeeded, the investment scale and timeline required demonstrate the magnitude of wholesale replacement efforts.

Why do these projects fail so consistently? It's not because COBOL is inherently bad or because modern languages are inadequate. They fail because organizations attempt to replace systems they don't truly understand. As one modernization expert notes , "A very common mistake is underestimating the effort required to port code from COBOL... changing this code for modernized platforms can be as complicated as a heart transplant."

Think about it: If you can't articulate precisely what your current system does, how it handles edge cases, what business rules it enforces, and why those rules exist—how can you specify what the replacement system should do? You can't improve what you don't understand. You can only recreate it blindly, hoping you've captured everything necessary.

The Hidden Value in "Legacy" Business Logic

Your COBOL systems aren't just old code. They're living repositories of institutional knowledge, containing business rules refined through decades of real-world testing. Every conditional statement, every calculation, every data validation represents a lesson learned—often the hard way.

Consider a typical accounts receivable system that's been running for 30 years. It handles customer payments across dozens of states, each with different tax regulations. It manages currency conversions with rules for rounding that comply with banking regulations from multiple countries. It includes special handling for VIP customers, seasonal adjustments for different industries, and exception logic for edge cases that occur only once every few years—but when they do, they matter enormously. Decades of edge cases live in black-box logic, scheduler graphs, and implicit data contracts that nobody has fully documented.

This logic wasn't designed in a conference room. It evolved through countless production incidents, compliance audits, customer complaints, and business requirement changes. Each line of code represents a specific business need that was important enough for someone to pay a developer to implement it. These battle-tested COBOL systems have proven their reliability over decades, with millions of lines of code tested extensively in real-world scenarios.

When organizations replace these systems without a deep understanding, they inevitably rediscover these requirements incorrectly: through production failures, compliance violations, and customer impact. The modern reimplementation goes live, and suddenly, invoices for customers in Montana are being miscalculated due to a tax rule nobody remembered to document. Or international payments start failing because the new system's rounding algorithm doesn't match banking standards.

What executives often call "technical debt" frequently means something else entirely: "We don't understand this anymore, and that makes us uncomfortable." — but that's not an argument for wholesale replacement. It's an argument for strategic understanding.

The Real Cost: Someone Must Bear the Cognitive Load

Here's the fundamental truth that no one wants to say out loud: one way or another, someone has to put in the cognitive effort to understand your code. This isn't optional. You're going to pay for this understanding whether you realize it or not.

You have three basic options:

- You can dedicate your own internal resources—pulling experienced developers away from new features and business initiatives to document and analyze decades-old systems painstakingly. This is expensive in opportunity cost, slow, and vulnerable to the same knowledge loss you're trying to prevent when those developers eventually leave.

- You can hire outside experts—specialized firms or independent consultants who bring deep COBOL expertise. They can accelerate the process significantly, but the cost is substantial, the timeline is measured in months or years, and the knowledge often walks out the door when the engagement ends.

- Or you can leverage new approaches that shift the cognitive load from humans to computers—AI-powered tools that can analyze millions of lines of code, trace data flows, extract business logic, and create searchable knowledge bases in weeks instead of years. This is a fundamentally different economic equation.

The question isn't whether you'll invest in understanding. The question is which approach gives you the best combination of speed, cost, and retained knowledge.

When Understanding Beats Replacement

Strategic understanding of your COBOL systems changes everything. When you can quickly answer questions like "What business functions does this program implement?" or "What would be impacted if we change this calculation?" or "Where is this regulatory rule enforced?"—you unlock genuine strategic options.

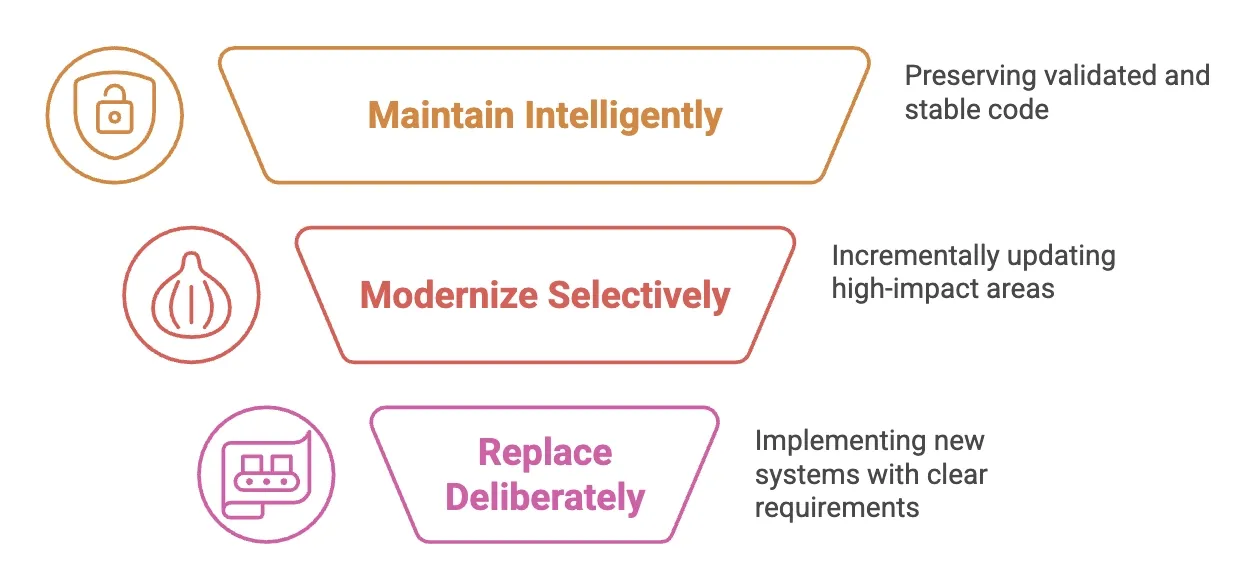

With deep understanding, you face three viable paths instead of one:

Maintain Intelligently: Some business logic is essentially perfect. It works, has been validated over years of production use, and handles every edge case correctly. Why recreate it? Understanding reveals which code to leave alone.

Modernize Selectively: Perhaps 20% of your codebase handles 80% of your business change requests. Understanding identifies these high-value modernization targets. The Strangler Fig pattern enables incremental modernization that gradually reduces the legacy system's responsibilities while expanding the scope of new systems. This approach reduces business risk by keeping critical systems operational during migration and enables continuous feedback loops that ensure early wins.

Extract and rebuild the pieces that constrain your business, while leaving stable, working code in place.

Replace Deliberately: When replacement makes sense, understanding provides the detailed requirements and specifications you need for success. You're not guessing what the new system should do—you know, with complete traceability to the business functions you're reimplementing.

The ROI calculation changes fundamentally when you know what you actually have. That $20 million modernization project might become a $3 million selective extraction effort—or a $500,000 knowledge capture initiative that makes your existing system manageable for the next decade.

The Technical Challenge: How Understanding Is Actually Achieved

For developers and technical architects wondering "how do we actually do this?", achieving deep COBOL understanding requires sophisticated engineering, not just good intentions. The technical challenge involves program slicing, data flow analysis, and business logic extraction—computational techniques that trace how data flows through programs and identify which code segments influence specific outputs.

The real modernization challenge isn't replacing COBOL with Java or Python. It's transforming trapped, inaccessible knowledge into strategic intelligence that anyone in your organization can understand and use—from developers to business analysts to executives.

When you can answer in minutes what currently takes weeks of code archaeology, you transform your relationship with legacy systems. What was an opaque liability becomes a transparent asset. What was a source of risk becomes a competitive advantage.

The modernization lie is that your value lies in your technology stack. The truth is that your value lies in your business functionality—the accumulated wisdom of thousands of decisions, refinements, and real-world lessons. That logic is what runs your business. The programming language it's written in is just syntax.

Before you write the next check for a modernization project, ask a more straightforward question: "Do we actually understand what we're trying to replace?" If the answer is no, that's your real problem—and understanding is a much better investment than replacement.

Your legacy systems aren't problems to be solved. They're knowledge to be unlocked.